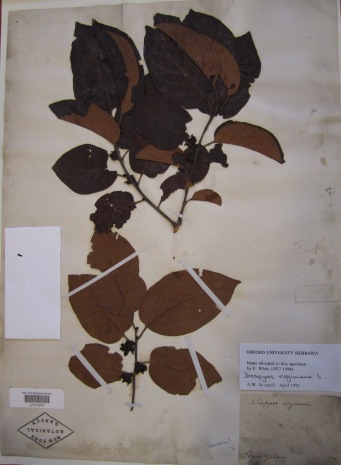

Specimen of Diopyros virginiana collected from the site of the Elgin Botanic Garden in 1829, New York Botanical Garden Steere Herbarium

Since the joint CBHL/EBHL meeting (see earlier post) was held in New York, it’s not surprising that there were several presentations related to the metropolis. It seems fitting to end this series of posts with a review of them. After a welcome from Susan Fraser, director of NYBG’s Mertz Library, the first major speaker of the conference was Eric Sanderson of the Wildlife Conservation Society, headquartered across the street from the New York Botanical Garden, at the Bronx Zoo. For many years Sanderson has had a leading role in research on what New York was like before Henry Hudson sailed into the mouth of the Hudson River in 1609. The indigenous people called the large island he found Mannahatta, and that became the name for Sanderson’s endeavor and the title of the book he published in 2009. Using mapping technology coupled with old maps, historical accounts of the area, specimens collected there in the past, and what is known about the ecology and geology of the island, Sanderson’s team identified 54 different ecosystem types on Mannahatta. This is a large number for that sized piece of land, and the result of its extensive wetlands along with its varied geological features. There were also an estimated 600 species of plants.

More recently Sanderson has led an effort to produce the same kind of modeling for New York City’s other four boroughs. Called Welikia, it too has a website that is still under construction, but includes all the information from the Mannahatta Project. These are not just interesting exercises in environmental history, they aim at helping the citizens of New York understand the biodiversity that once existed there and how to preserve and nurture as much of it as possible. It is unlikely that bears will again roam Manhattan, but red-tailed hawks are flourishing (Winn, 1998), and I’ve seen a coyote ambling inside NYBG’s fence as I was stuck in traffic trying to get there.

On the second day of the conference, the botanical illustrator Bobbi Angell presented on the formidable botanical art collection housed at NYBG. Angell has spent her life creating pen-and-ink drawings to illustrate the scientific work of the garden’s botanists, including many for the seven volume Intermountain Flora: Vascular Plants of the Intermountain West, USA. The last volume was just recently published (2017) and includes not only some of Angell’s illustrations but biographies of her and other illustrators and botanists who worked on this project that was first envisioned by Bassett Maguire in the 1930s. There will be more on the editors, Patricia Holmgren and Noel Holmgren, in a future post.

Angell didn’t dwell on her accomplishments, but instead discussed some of the other contributors to the 30,000 pieces in the NYBG art collection. These include the great French botanical painter Pierre-Joseph Redouté with 10 paintings on linen, but Angell concentrated on 20th and 21st-century artists, including Alexandria Taylor and Frances Horne who did illustrations respectively for Elizabeth Britton and Nathaniel Lord Britton. Both were distinguished botanists and Britton was NYBG’s founding director. Angell spoke reverently of artists whom she knew including Anne Ophelia Todd Dowden, who left her finished works to the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation in Pittsburgh, and her working drawings to NYBG, an interesting division. Then there was Rupert Barneby a self-taught botanist and artist who did research at the garden and became an expert on legumes. He created his own illustrations until he injured his hand. Angell ended with a plea for more of the botanical art in library collections to be made available online and a mention of the American Society of Botanical Artists, which has a wonderful journal for members as well as a website on which they can present their work.

The final presentation of the meeting was a public lecture by Victoria Johnson to celebrate the publication of her book, American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic (2018). She began the book and her talk very effectively by telling the story of how David Hosack, a physician, treated a New York boy dying of fever in 1797. Hosack had tried everything he could without success, and so decided to lower the boy into warm bathwater with cinchona bark mixed in. Several of these treatments led to the patient’s recovery and to a tearful thank you from his father. Johnson then paused, and revealed that the father was Alexander Hamilton. After this surprise, she went on describe some of what she writes about in her book: how Hosack trained as a physician in the United States and Britain where he developed an interest in botany, even studying with James Edward Smith the founder of the Linnean Society; how he set up a medical practice in New York, obviously attracting an elite clientele; how he developed a plan to create a botanical garden in the city as a way to nurture, study, and teach about medicinally useful plants. He used his own money to buy 20 acres of land in what is now midtown Manhattan, but was then over three miles north of the city. He called it the Elgin Botanic Garden after the Scottish town where his family originated. He built a wall around the property as well as greenhouses and then bought an impressive selection of plants.

Hosack had a long and successful life as a physician, but his story is definitely bittersweet. He was the attending physician when his friend Alexander Hamilton was shot in the duel with Aaron Burr (it turns out they both were interested in gardening). The garden, begun in 1801, was destroyed in the 1820s after it had been bought by New York State and then handed over to Columbia College (now Columbia University) for management. It was neglected and eventually leased by Columbia as real estate prices in that part of Manhattan started to soar. Eventually, it became the site of Rockefeller Center. However, to end on a happier note, there are a few Elgin Garden specimens in the NYBG herbarium including Diosyros virginiana (see above).

Note: I would like thank all those involved in the wonderful CBHL/EBHL meeting, particularly Susan Fraser, Kathy Crosby, Esther Jackson, and Samantha D’Acunto. I am also grateful to the participants from whom I learned so much, to Pat Jonas who nudged me to attend, and to Amy Kasameyer who introduced me to CBHL.

References

Holmgren, N. H., & Holmgren, P. K. (2017). Intermountain Flora: Vascular Plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A (Vol. 7). New York, NY: New York Botanical Garden.

Johnson, V. (2018). American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic. New York, NY: Norton.

Sanderson, E. W. (2009). Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City. New York: Abrams.

Winn, M. (1998). Red-Tails in Love: A Wildlife Drama in Central Park. New York: Pantheon.