The title of this post is meant to differentiate it from my last post, “Herbaria in Libraries,” which described bound herbaria kept in library special collections. There are many of these, particularly in Europe where almost all of the oldest herbaria are found. The case I want to describe here is different: an entire herbarium now resides in the West Chester University Francis Harvey Green Library’s Special Collections vault. It used to be housed in the biology department, but its only botanist was retiring, and the department could wanted to use the space for other purposes. To anyone familiar with the history of herbaria, this is an all too common story, but here the outcome was not moving the collection to one or more other institutions as usually happens.

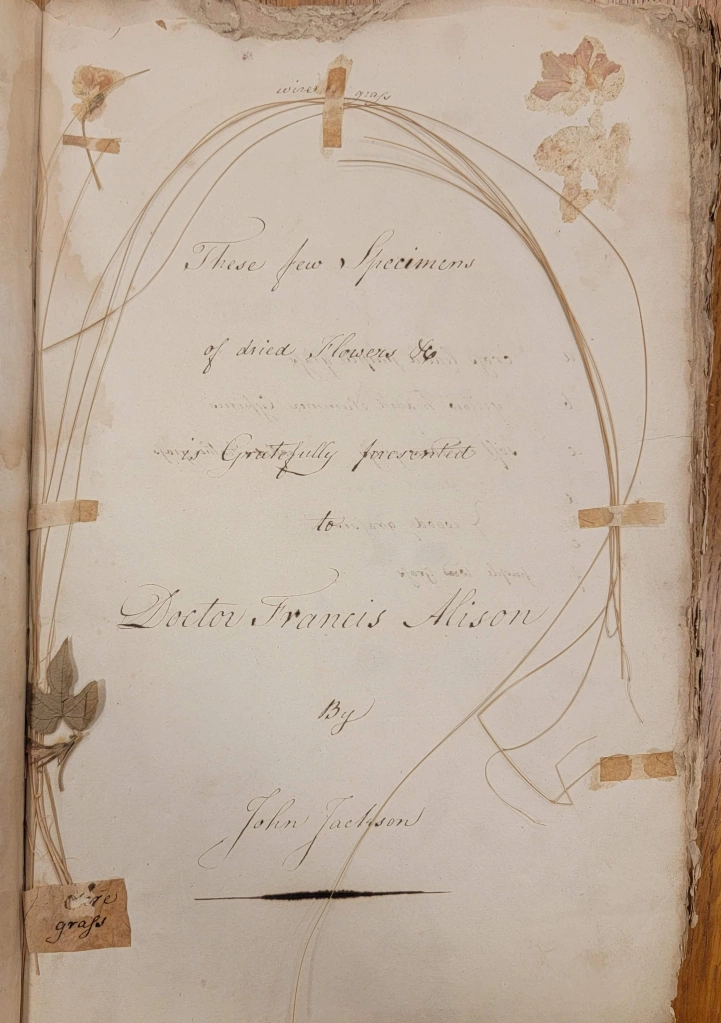

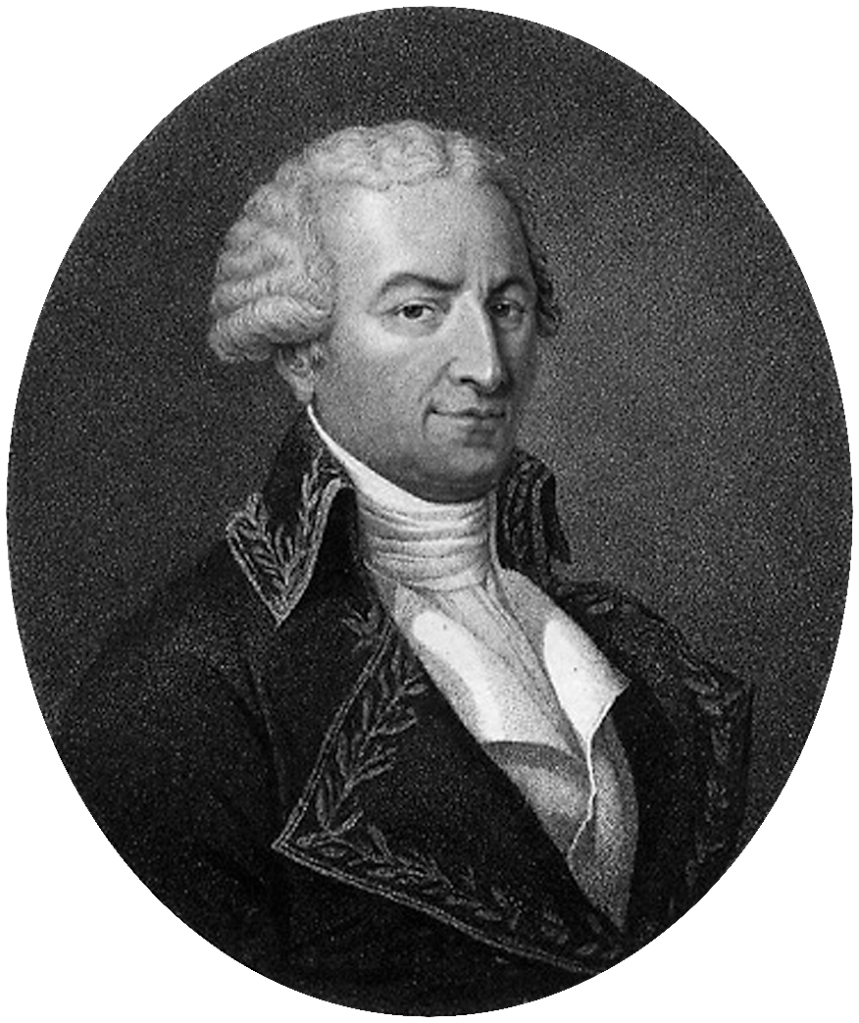

One of the reasons for this is that the herbarium, named after William Darlington (1782-1863), houses specimens that are among the oldest in the United States and are closely related to the West Chester area. Darlington, a native of West Chester, was a physician and botanist, who was also one of the founding members of the Chester County Cabinet of Natural Sciences in 1826. At the time Chester County already had a rich botanical history since it was home to John Jackson whom I mentioned in the last post and to Humphry Marshall who had a conservatory and botanical garden on his farm and sold North American trees and shrubs to European collectors. His Arbustum Americanum: The American Grove (1785) was the first botanical book produced in America written by a native-born American on American plants. Though he died in 1801, his garden remained for some time, and Darlington had plants from there in his herbarium. He also had specimens collected on the Peirce family forest land, which later became Longwood Gardens and from Bartram’s Garden during the time it was being managed by John Bartram’s descendants (Schneider, 2009).

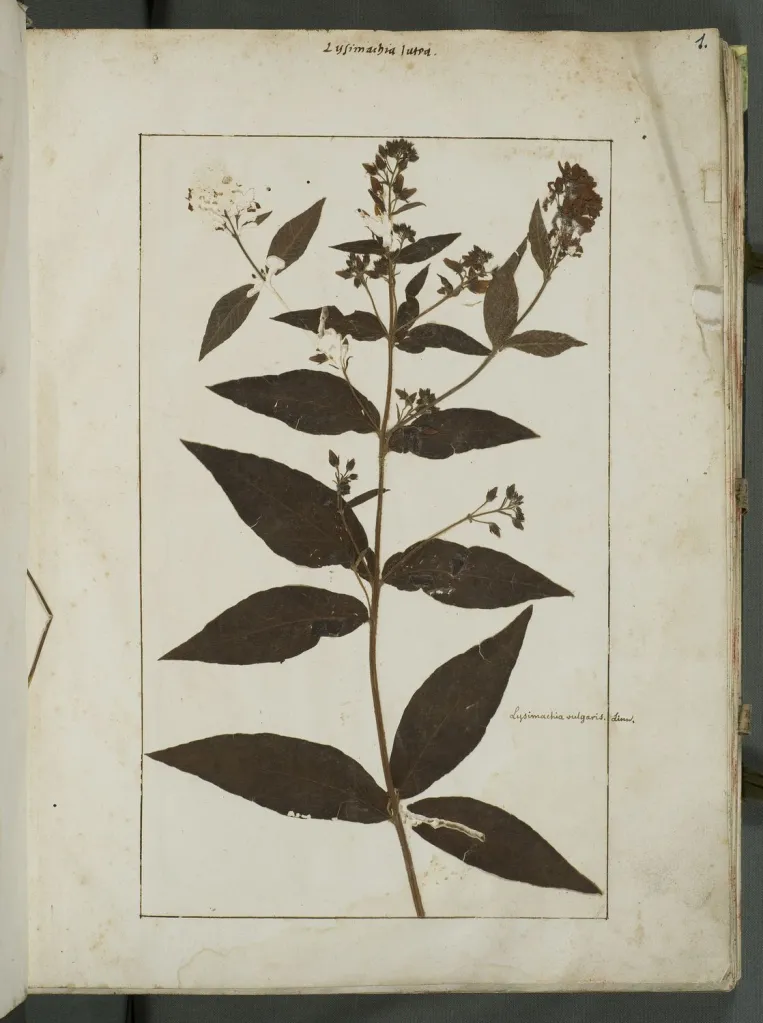

When I was beginning my herbarium investigations, I gave a talk at the Botanical Society of America’s annual meeting and afterwards a woman suggested I visit West Chester because they had a great historical collection. I am very sorry that I don’t recall her name because I would love to thank her for the suggestion. I first visited in 2012 and the curator Sharon Began was very welcoming and helpful. I had a wonderful time looking at specimens collected by Constantine Rafinesque, William Baldwin, Elias Durand, and Edward Tuckerman. But there was more, Darlington corresponded and traded specimens with Charles Short, John Torrey, and Asa Gray in the United States and William Jackson Hooker, Augustin de Candolle, and Carl Agardh in Europe. He opened correspondence with many of these by sending each a copy of the flora of West Chester that he first published in 1826.

During that same visit, I met McColl who was then technician in the university’s special collections and already had a serious interest in Darlington, who had been a major figure in the life of West Chester well beyond his botanical interests. He was a physician for most of his career, having studied at the University of Pennsylvania under the botanist Benjamin Barton. He was also important to the political and economic life of West Chester. He served three terms as congressman as well as being president of the local bank and railway. Special Collections has several of his letter books where he copied out his correspondence with such notables as de Candolle and Lady Dalhousie, botany enthusiast and plant collector as well as wife of the Governor General of Canada. I had a great time, was hooked on learning more ,about Darlington and ended up writing an article about how John Torrey (1853) came to name the pitcher plant Darlingtonia californica after him (Torrey, 1853).

This required a few more trips to West Chester, but I hadn’t been there in several years and so hadn’t seen the herbarium in its new quarters. When McColl learned of the biology department’s plans, he did a little measuring and figured out how he could store most of the herbarium’s cabinets in the special collections vault. They just fit. Also in the vault are the hundreds of books that were in Darlington’s library, including many of the great botanical resources of the 18th and 19th centuries, among them an edition of Linnaeus’s short works that had been given to John Bartram and passed on to Darlington by one of Bartram’s descendants. This book may have been a gift in recognition of Darlington’s publishing a twin memorial on Humphry Marshall and John Bartram based on papers shared with him by members of both families . McColl argues that this publication, along with a memorial to the botanist William Baldwin who was a good friend, make him a significant early chronicler of American botany.

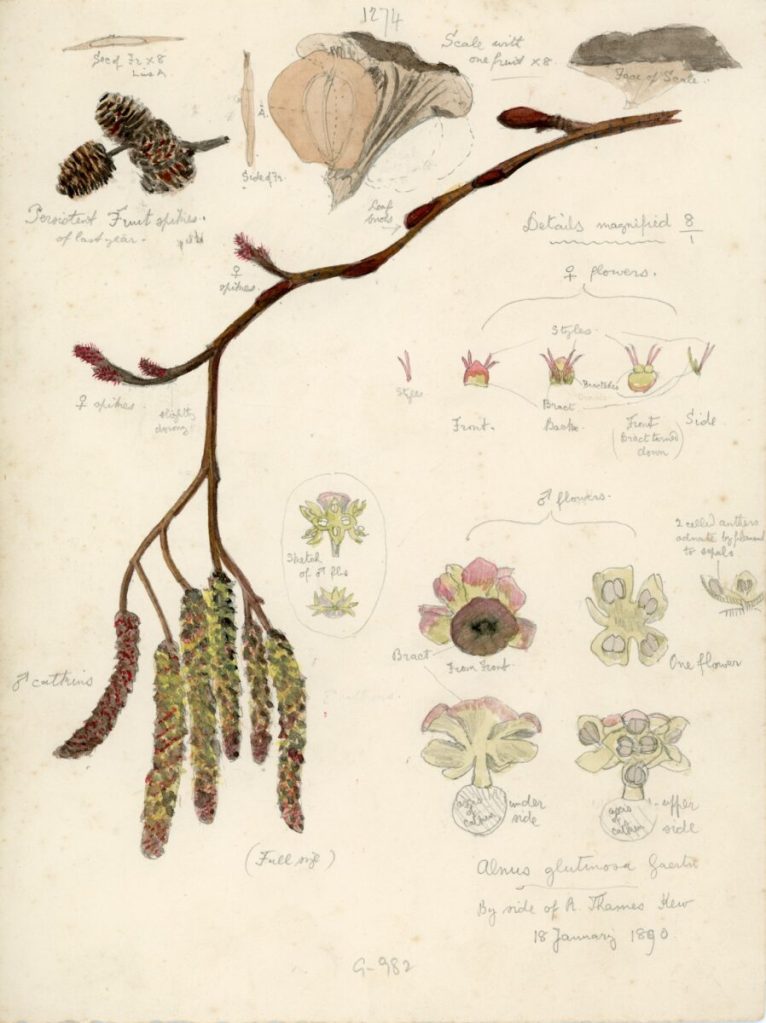

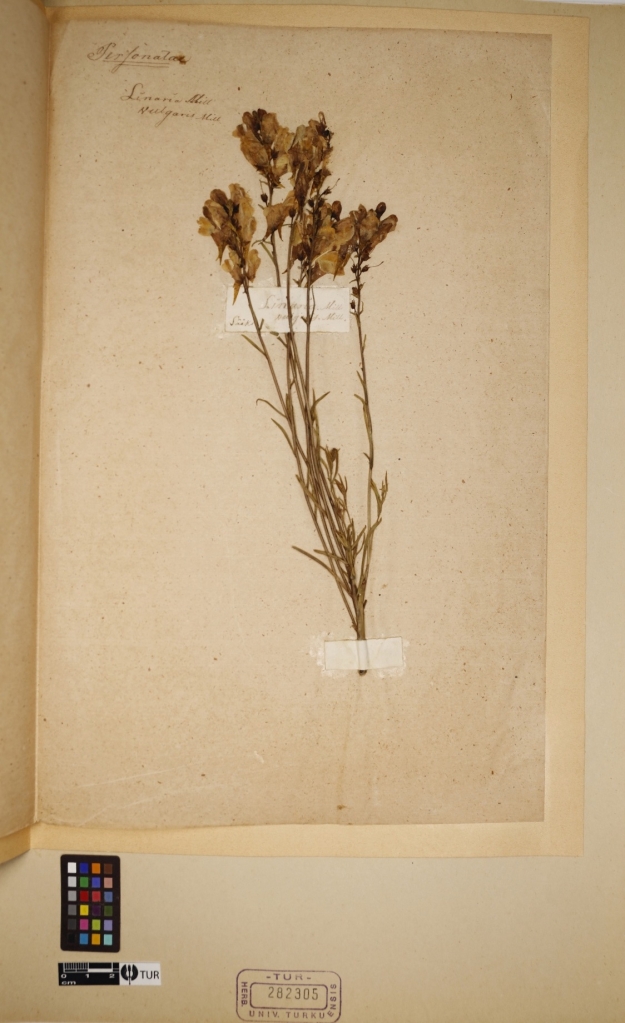

What caught my eye on my first visit to the collection were the notes that Darlington had attached to many of his specimens, including some that were of personal importance. One was on a specimen of Darlingtonia brachyloba, a plant de Candolle had named after him. It was collected in 1847 from “the tomb of my blessed wife.” He did not note that this name had been synonymized to Desmanthus brachyloba (now Desmanthus illinoensis) in a 1841 publication by the British botanist George Bentham, even though he knew all about it. When Torrey told him of naming the pitcher plant after him, he wrote back to him fearful that the “odious” George Bentham would do the same to this plant since he had just published a description of a new pitcher plant. In the herbarium there’s a copy of the Torrey’s publication of the species and a letter from him assuring Darlington that the name was safe. Torrey even went to the trouble of including a tracing of the illustration in Bentham’s paper, along with a copy of the legend. I think you can see that Darlington’s herbarium is as much archive as herbarium and has found an appropriate home where, I might add, McColl has had the entire collection digitized over the past few years.

Notes: I am very grateful to Ron McColl for taking the time to show me so many treasures.

References

Schneider, W. M., & Potvin, M. A. (2009). The historic Bartram’s (Carr’s) Garden Collection in West Chester University’s William Darlington Herbarium (DWC). Bartonia, 64, 45–54.

Torrey, J. (1853). On the Darlingtonia californica, a new pitcher-plant from northern California (pp. 1–11). Smithsonian Institution. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/15291