Title page of The Gardeners Dictionary (8th ed) by Philip Miller. Biodiversity Heritage Library

One of my favorite botanically flavored books is Andrea Wulf’s (2011) Founding Gardeners about the horticultural pursuits of Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. This book grew out of her earlier study (2009), The Brother Gardeners, which deals primarily with the gardening scene in 18th-century Britain. This subject is very much tied to North American botanical exploration and to the systematics of Carl Linnaeus, who in various ways has been the subject of my last two series of posts. The present series deals with the excitement about botany present in the 18th-century, and Linnaeus appears again here. His classification scheme, fundamentally based on counting the male and female structures in the flower, made it much easier to identify a species. No longer was a plant lover required to know a great deal of terminology and to sift through a large number of characteristics as the natural systems of John Ray and Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, for example, required. Linnaeus also corralled nomenclature by christening each plant with a two-word appellation: genus and species. Many of us still find the Latin names of plants a challenge, but think what it was like when there was a string of six or more Latin words to designate a species.

Linnaeus does not deserve all the credit for the burgeoning interest in plants at this time. Paper and books were becoming cheaper and more accessible, and literacy rates were rising so more people had the opportunity to learn about botany. Philip Miller, the head gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden in London, published the first edition of The Gardener’s Dictionary in 1731 and became a driving force in the popularization of plant information; the book ran to eight editions during his lifetime. The science of botany was developing as universities like Oxford and Cambridge created botany faculty positions and botanical gardens. Then there was the surge of new plants coming into Europe from explorations around the world. While these had been going on since the 16th century, the expeditions became larger and the hunt for new plants better organized. Each of James Cook’s three voyages around the world involved teams of artists, naturalists, and geographers, most famously on the first trip when Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander collected plants and animals, which were then drawn by Sydney Parkinson (O’Brian, 1993). The French sent a similar team on the ill-fated La Pérouse expedition, which was followed by a similarly equipped one led by Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux (Williams, 2003), while the Spanish mounted several large, long-term expeditions in the later part of the century (Bleichmar, 2011).

Yet all these sources of plants didn’t seem to be enough to satisfy gardeners. One problem was that many plants were sent to Europe only as pressed specimens, and often languished between sheets of paper for years, if not for centuries, as was the case with some of the material from the Spanish Sessé and Monciño Expedition (McVaugh, 2000). There were efforts to send back seeds and seedlings, but these materials often moldered on long voyages or failed to thrive in the European climate. Still, nurserymen and avid gardeners persisted. One of the most successful horticultural enthusiasts was Peter Collinson, a British Quaker and textile merchant, who successfully grew such exotics as a North American pitcher plant that had been described a century earlier, but was never induced to flower until he nurtured it (Wulf, 2009). Collinson was well connected with upper-class gardeners of the day, from his fellow Quaker, the physician John Fothergill, to Lord Bute, one time British Prime Minister and adviser to the young King George III. While Americans don’t have fond memories of the king, he was an ardent horticulturalist, thanks to Bute and to Joseph Banks, who served as his unofficial botanical adviser in charge of Kew Botanic Gardens.

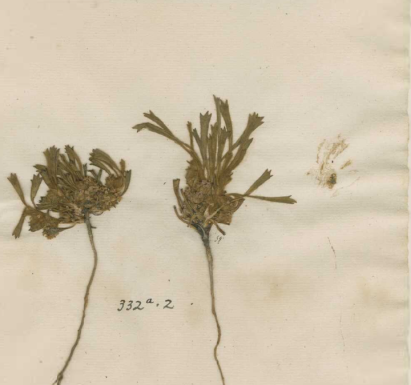

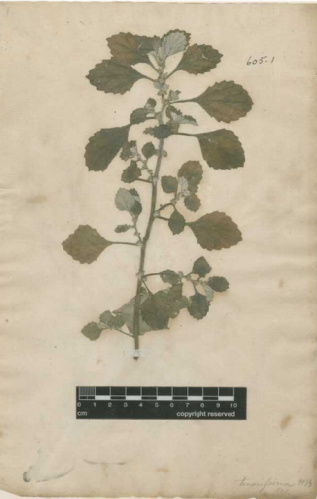

Collinson linked his horticultural to his business interests by asking his textile customers in the American colonies for help in obtaining New World plants. His most long-term and fruitful contact was with the Quaker farmer, John Bartram, in Philadelphia. Once they started to correspond, Bartram began sending seeds, specimens, and cuttings to Collinson. In turn, Collinson sent Bartram exotics from other parts of the world including the Chinese aster, Callistephus chinensis, which was brought back to France by Jesuits missionaries and from there sent to England, an indication of how seeds wandered around the world (Laird, 2015). Since Bartram’s botanical knowledge, though growing, was limited, he would make two sets of specimens for each type of seed he sent, using a number code to keep track of them. Collinson would then identify the specimen, or have someone like the Oxford botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius do so, then send the information back to Bartram who then labeled his sheets accordingly.

Collinson also encouraged Bartram to travel through the colonies to find new species. This is how the latter and his son William discovered such gems as Franklinia alatamaha. In Britain, Collinson organized a group of patrons—more than 50 over the years—who paid for boxes of seeds and seedlings from Bartram (O’Neill & McLean, 2008). The most avid of these was Lord Robert Petre (1713-1742), whose 16-volume herbarium contains many Bartram plants (Schuyler & Newbold, 1987). Petre planted thousands of Bartram-supplied tree seeds and seedlings, including 900 tulip poplars. Unfortunately, Petre died young. His estate was such a rich source of exotic species that other nobles vied to buy plants from his widow, such was the feverish state of British horticultural at the time (Wulf, 2009). But by the time Bartram died in 1777, American species had become commonplace in Britain and were supplied by British nurserymen. Bartram’s son, John Jr., who continued the business, then sold mainly to American gardeners who had caught the gardening bug from their former rulers.

References

Bleichmar, D. (2011). Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

McVaugh, R. (2000). Botanical Results of the Sessé and Mociño Expedition (1787-1803). Pittsburgh, PA: Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation.

O’Brian, P. (1993). Joseph Banks: A Life. Boston, MA: Godine.

O’Neill, J., & McLean, E. (2008). Peter Collinson and the 18c Natural History Exchange. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society.

Schuyler, A. E., & Newbold, A. (1987). Vascular plants in Lord Petre’s herbarium collected by John Bartram. Bartonia, 53, 41–43.

Williams, R. L. (2003). French Botany in the Enlightenment: The Ill-Fated Voyages of La Perouse and his Rescuers. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Wulf, A. (2009). The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire and the Birth of an Obsession. New York, NY: Knopf.

Wulf, A. (2011). Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation. New York, NY: Knopf.