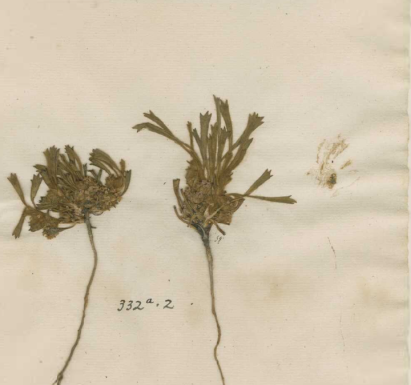

Solandra tridentata (LINN 332.2) from the herbarium of the Linnean Society, London

In the last post I discussed one of Carl Linnaeus’s students, Peter Forsskål, who never returned from his expedition to the Near East. Daniel Solander (1733-1782) traveled farther and also lived to study the fruits of his exploration. He was born in Lapland and, not surprisingly, studied in Uppsala where he was considered Linnaeus’s favorite pupil. When British botanists asked Linnaeus to send someone to England to boost the use of Linnaean taxonomy, Solander was chosen. He left in 1760 and never again lived in Sweden. At first, he spent time reorganizing the herbaria of wealthy patrons such as the Duchess of Portland and Peter Collinson, who was one of those who had encouraged Linnaeus to send an “apostle” to England. He was influential in British botanical circles as a member of the Royal Society, a trustee of the newly formed British Museum, and a patron of the American nurseryman John Bartram. Solander sent specimens from Collinson and others on to Linnaeus. When the British Museum was looking for someone to care for the herbarium of Hans Sloane, the donor of the museum’s founding collection, Collinson asked Lord Bute, then Prime Minister, to suggest Solander to the King as the ideal choice (Rose, 2018). This is a fascinating, though tiny, piece of history because all of the individuals involved were interested enough in plants that the care of a plant collection would be discussed at the highest government levels.

Solander began working at the museum in 1763 and set about giving the plants in the herbarium Linnaean names without disrupting the physical order of its 265 bound volumes. This was a compromise that would allow those not familiar with the new system to still find plants in the collection using Sloane’s system, which was essentially an annotated copy of John Ray’s Historia Plantarum in which Sloane or his botanical curator had written the volume and folio numbers for each species, noting new species when necessary. Solander began with the first volumes of the herbarium, those containing the collections Sloane had made while he served as physician to the Duke of Albemarle on the island of Jamaica in 1687-1688. Among the 800 species were hundreds of new ones that Sloane described in his two volume Natural History of Jamaica (1702-1727). Solander wrote the names on labels that he added to Sloane’s sheets, but retained the older labels, an approach that not been taken by many earlier botanists though later became the norm.

While at the museum, Solander began to receive visits from a young botanical enthusiast, Joseph Banks, heir to a large fortune who had attended but not graduated from the University of Oxford. He supplied Solander with an unmarked copy of the Sloane Jamaica volumes to annotate. This was a good way to keep track of the Jamaican species. When Solander moved on to the rest of the collection, he used slips of paper to record the new names and crossreferenced them with the volume and folio numbers. He also annotated a copy of Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum. In this way, the collection was “modernized” without being rearranged. This went on until 1768, when Solander took on a very different kind of challenge.

Banks had convinced the British Admiralty to make him part of the round-the-world expedition to be led by James Cook on the Endeavor. It’s major aim, and the publicized one, was to observe the transit of Venus across the sun, which would take place on June 3, 1769. However, Cook was also instructed to visit Australia, acquiring as much navigational and geographic information for future use in possible colonization (O’Brian, 1993). Banks, at his own expense, put together a team to study natural history. It included Solander, Herman Spöring of Finland as secretary, two artists, and two servants. Banks paid to outfit the ship for his group as well as for scientific instruments and other supplies for preserving specimens and even for growing plants. There is obviously a lot to this story, but for now I will stick to Solander and plants.

Apparently Banks and Solander made a good team. They developed a system for dealing with the huge amount of material they collected, in all, about 30,000 plant specimens. They would return to base each day, give the artist Sydney Parkinson the fresh material to sketch and make color notes, while they, with Spöring’s help, wrote up their notes. The plants were pressed, though at times, as when they reached Australia, their system couldn’t keep up with collecting. Plants weren’t drying fast enough, so the pair laid them out on deck on sails during the day. Needless to say, this massive collection proved daunting to tackle for publication. Banks and Solander worked on it for years, with engravings made of about 800 species from the Parkinson drawings. The artist hadn’t survived the voyage, but he did produce 900 complete watercolors and as well as hundreds of sketches. Unfortunately, Solander died in 1782 before the project was completed, and Banks seems to have given up first-hand work on botany after his death. Instead, Banks became more involved in projects to promote botanical exploration as well as agriculture. The Banks’ Florilegium wasn’t published until the 1980s in 34 massive volumes. Solander did not publish much but he was obviously essential to the Endeavour mission, and perhaps even more importantly, to making the Sloane Herbarium a continuingly useful botanical resource.

References

O’Brian, P. (1993). Joseph Banks: A Life. Boston, MA: Godine.

Rose, E. D. (2018). Specimens, slips and systems: Daniel Solander and the classification of nature at the world’s first public museum, 1753–1768. The British Journal for the History of Science, 5 (2), 1–33.