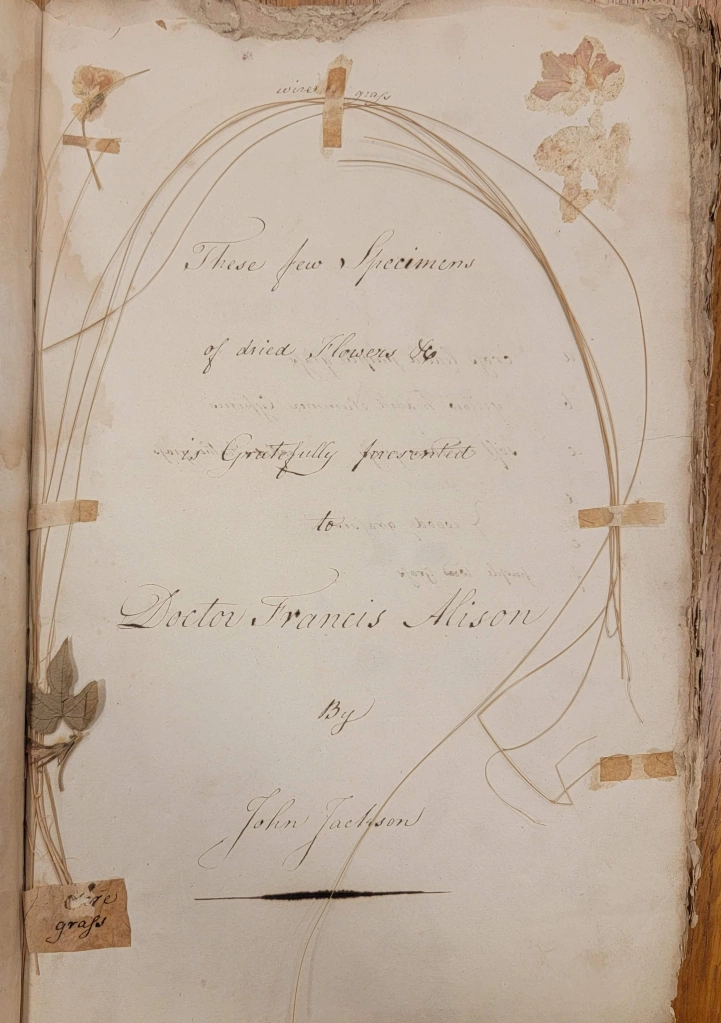

The final library I visited on my recent tour (see earlier posts 1,2,3) is my absolute favorite, the Oak Spring Garden Library in Virginia. It is the home of Rachel Mellon’s superb collection of plant-related books and art. It is a beautiful space and all the people I know who are connected with it are absolutely wonderful, from the President of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation Peter Crane to its librarian Tony Willis, as well as Kimberley Fisher, Nancy Collins, and Danielle Eady. They are all great—and the books are too. On this visit I looked at an illustrated manuscript copy of Konrad von Megenberg’s Buch der Natur from about 1350 and a 1455 Italian herbal by an unknown artist. It was a great experience to examine them, but for me, the real treasure in the collection is the Johannes Harder’s 1595 herbarium, which, oddly enough I did not examine on this trip.

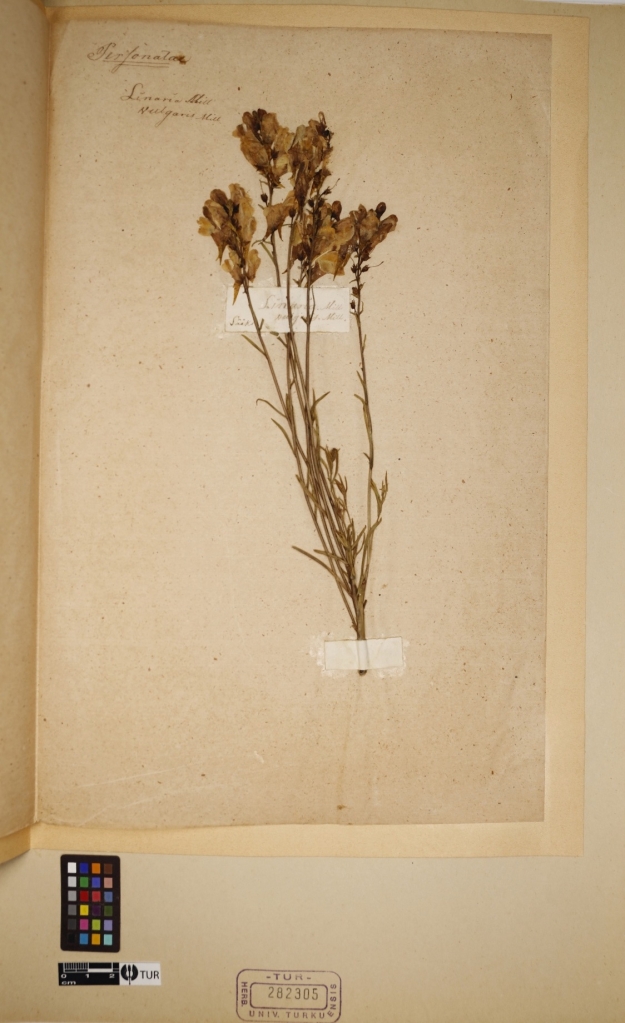

I didn’t need to disturb what is a very fragile work because the library is in the process of digitizing its manuscripts, and though they aren’t available online yet, Peter Crane very kindly allowed me to have low resolution images to use for my research. This is a great relief because I can examine the manuscript’s contents without disturbing its pages. There’s a great deal to study here, even though most pages have little more than the Latin and German plant names, sometimes with Polish names added at a later date. I fell in love with this because Harder added watercolor embellishments to most of its pages. These range from painting-in missing petals to entire flowers, roots, and bulbs. The most common addition is a clump of grass-covered earth to ground the stem. His work is not unique. There are twelve of his father Hieronymus’s herbaria in European institutions as well as one by his brother-in-law Johann Brehe (Skružná et al., 2022) and at least one more by someone else from the same area in Germany (Dobras, 2013). Hieronymus seems to have originated the style, and it became one of several early experiments in how best to preserve information about plants from storing illustrations and specimen together to creating nature prints.

While this experiment didn’t catch on, it is nonetheless fascinating. It also got me thinking about the herbarium not just as a document of botanical information or as an historical document, which it certainly is, or even as a piece of art, but also as a manuscript. I am not the only one thinking this way. Bettina Dietz, a researcher at the University of Erfurt in Germany has written an article on the herbarium as manuscript, in which she focuses not on the specimens themselves but on the written information on the sheets (Dietz, 2024). After all most manuscripts are seen as written documents, and Dietz doesn’t consider these pages as an exception. She examines the bound herbaria that the German botanist Paul Hermann (1646-1695) created during his years as a medical officer in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. Two of the volumes have extensive notations by him and by later owners. There is information on the indigenous language and its script as well as notes on the medicinal uses of the plants and their morphology. Dietz does a textual analysis similar to what would be done on other manuscripts. She argues that these writings tell a great deal about both the botanical knowledge and the linguistic skills of the authors.

When I saw her title I was expecting something a little different because for several years I too have been thinking about early herbaria as manuscripts, but from another perspective. This occurred to me during covid when I read a blog post by a Dutch graduate student Suzette van Haaren who was researching the relationship between the digitized version and the physical one for among other manuscripts the Bury Bible at Cambridge University. She was at Cambridge, but couldn’t access the “real” bible and wrote about how she navigated that divide. This intrigued me, and since I had time to think and to explore manuscripts on the web I learned about how they are digitized. It is a very different process than imaging specimens. Because of the irregularity in the pages due to staining, warping, and different kinds of images, some with gold embellishments, each page requires individual attention. Digitizing specimens was about getting good images of as many specimens as possible to the point that it could be done on an assembly line. Digitizing manuscripts bordered on art and required a different set of skills that would apply to early bound herbaria as well.

There are many other similarities between manuscripts and bound herbaria dealing not with the text or even with digitization, but with the very materiality to the sheets. Study of this aspect can tell many stories. The Harder herbarium pages are watermarked, and a librarian friend was able to trace the mark to a German papermaker of the era and working in an area close to where Harder lived. The pencil lines on the left and right hand sides of each page suggest that Harder was knowingly imitating the structure of a manuscript’s border, as does the index that has each page divided into three columns with lines in red that also run across the top and bottom of the page. Harder’s writing is calligraphic with carefully done capital letters, and the watercolor drawings are similar to those in early herbals. I could go on about the feel of the paper and the look and feel of the well-warn binding with what are left of brass fittings. It is in this physicality that digitized versions fail miserably, but I am still very grateful for them because how else would I have ever seen the great En Tibi herbarium in Leiden or Ulisse Aldrovandi’s in Bologna.

Note: I am very grateful to everyone at the Oak Spring Garden Library for making my visit so wonderful, as it always is.

References

Dietz, B. (2024). Herbaria as manuscripts: Philology, ethnobotany, and the textual–visual mesh of early modern botany. History of Science, 62(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/00732753231181285

Dobras, W. (2013). Hieronymus Harder und seine zwölf herbare. Montfort, 65(2), 121–152.

Skružná, J., Pokorná, A., Dobalová, S., & Strnadová, L. (2022). Hortus siccus (1595) of Johann Brehe of Überlingen from the Broumov Benedictine monastery, Czech Republic, re-discovered. Archives of Natural History, 49(2), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.3366/anh.2022.0794