In this series of posts (1, 2, 3), I’ve discussed projects undertaken by the Dumbarton Oaks Museum and Library in Washington, DC. It is affiliated with Harvard University and is known for outstanding scholarship in three areas: Gardens and Landscape, Byzantine, and Pre-Columbian studies. One result is the book Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Batsaki et al., 2017) that grew out of a 2013 conference; online and onsite exhibits also accompanied the conference, so it’s obvious why I used “multimedia communication” in the title for this post. Dumbarton does a very good job of leveraging the scholarship it produces to speak to a variety of audiences through time and space. There are other examples of its productions, but this is one that’s about botany and particularly interests me.

Historians sometimes use the adjective “long” for a century, wanting to stretch one beyond 100 years to fit the topic they are covering. This is an example of how human categories don’t always meet human needs, or describe the real world. Expanding the eighteenth century here allows coverage to include some of William Dampier’s early botanical collecting, including plants in Western Australia in 1699; these were the first from that continent. Johannes Commelin (1629-1692) would not seem to belong, but in his work as director of Amsterdam’s Hortus Botanicus, he began a project to publish on what was growing in the garden, including the many plants that were coming into the Netherlands from Dutch colonies in South America, South Africa, and Asia. After he died, his nephew Caspar Commelin Jr. completed Horti medici amstelodamensis (1697–1701).

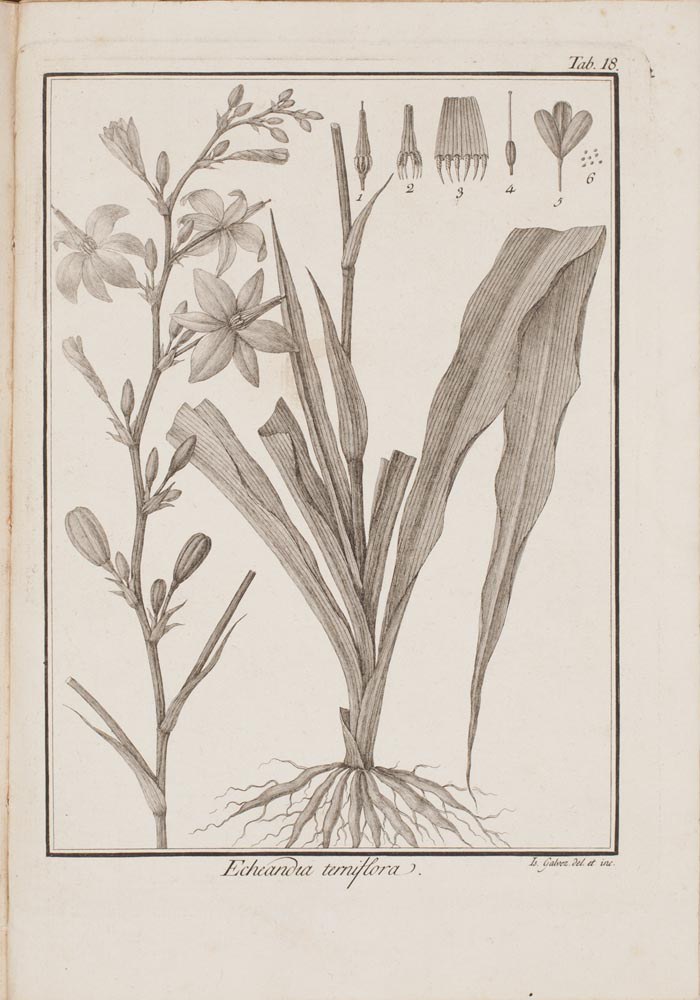

Expanding the other end of century made it possible to treat the series of Spanish expeditions running from 1770-1820 and designed to investigate the botanical wealth in its colonies almost three centuries after they were first established (Bleichmar, 2011). Earlier the emphasis had been more on exploiting mineral wealth, but the director of Madrid’s botanical garden convinced the king that plants from the species rich tropics could also be lucrative. Potatoes, maize, and tobacco had become major sources of wealth for many nations, why shouldn’t Spain benefit from “home grown” resources.

It would have been a shame for the conference to ignore Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland’s private expedition to Latin America in 1803-1808 (Wulf, 2015). For a variety of reasons, the Spanish projects did not yield as rich a result in terms of economic botany or even botanical publications as might be expected from the number of botanists who participated, the specimens collected, and the illustrations produced by both European and indigenous artists. On the other hand, Humboldt produced over 20 publications, some with assistance from Bonpland. These included seven volumes on plants as well as the Essay on the Geography of Plants that opened up the field of botanical geography, which had been developing in the background and with Humboldt’s analysis and illustrations became a significant theme in the 19th century.

Such century expansion wasn’t really necessary because there was so much botanically important work produced in those hundred years. Carl Linnaeus and his traveling students’ plant collections fit snuggly in here, as do James Cook’s voyages around the world, and Mark Catesby’s trips to the American Colonies and his illustrated masterwork, The Natural History of the Carolinas, Florida and the Bahama Islands. But what I like most about the book are all the topics covered that I didn’t know anything about, including a plan presented to the French National Assembly in 1790 by Louis-François Jauffret to create models of all 25,000 known plant species. He argued that these would be better than other representations because they would be three-dimensional. He noted that at the time, botany had to deal with old, dry, pressed plants. Jauffret had enlisted the assistance of Thomas Joseph Wenzel, Marie Antoinette’s florist, who had made many beautiful blooms often used to decorate her dresses. I am very sorry that nothing came of this project (Tessier, 2020).

There are also essays on the development of botany in 18th century Russia, Ottoman horticulture, and Mongolian medicine. Putting all these pieces and many others together created for me a much richer view of plants in that time period. Unfortunately, I did not see the exhibition at Dumbarton, but I have spent a good deal of time with the digital exhibit and have been dipping into it as I’m writing this post. It is a luxury to be able to visit a presentation that was created over eight years ago. Many digital exhibits of that “era” are no more than dead links now. It is a credit to Dumbarton that its valuable materials are still online. It is a sophisticated presentation, but easy to navigate. And if the exhibition were staged today, I am sure there would be online seminars as well, like the ones held in conjunction with the Margaret Mee exhibit (see last post). I’ll end by saying that there is NO substitute for a visit to Dumbarton to see the museum and garden. There is also no substitute for looking at items from its library and archives. However, many of its treasures have been digitized and there is a guide to the collection.

References

Batsaki, Y., Cahalan, S. B., & Tchikine, A. (2017). Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bleichmar, D. (2011). Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tessier, F. (2020). Modèles botanique, des modèles scientifique entre art et science. ISTE OpenScience, 1–19.

Wulf, A. (2015). The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. New York: Knopf.