In the world of herbaria, Duke University’s decision to close its herbarium has had a major impact. Many leaders in the field have risen in defense of these preserved plant collections including Harvard University’s Charles Davis, a leading advocate for herbaria (Davis, 2023), the stellar science writer Carl Zimmer, and Emory University’s Cassandra Quave, author of an award-winning book on ethnobotany (Quave 2022). National Public Radio’s Meghna Chakrabarti weighed in by interviewing Duke Herbarium director Kathleen Pryer. In each instance, the stress was rightly put on the importance of these collections in documenting biodiversity and dealing with climate change issues.

I definitely agree with this emphasis but I see herbaria as making more far-reaching contributions. Not only are they used by biologists and environmentalists, but by historians, artists, writers, gardeners, and students. This is not surprising since herbaria can make an important contribution to a community’s culture. In the NPR presentation, there was a sound bite from Dean of Natural Sciences at Duke Susan Alberts, who compared the herbarium to the university’s library, with both being university repositories, but the library serves the broad community while the herbarium a very small one. I’d like to note that the library also takes a much larger chunk of Duke’s budget, and an herbarium can serve a significant portion of a university’s community.

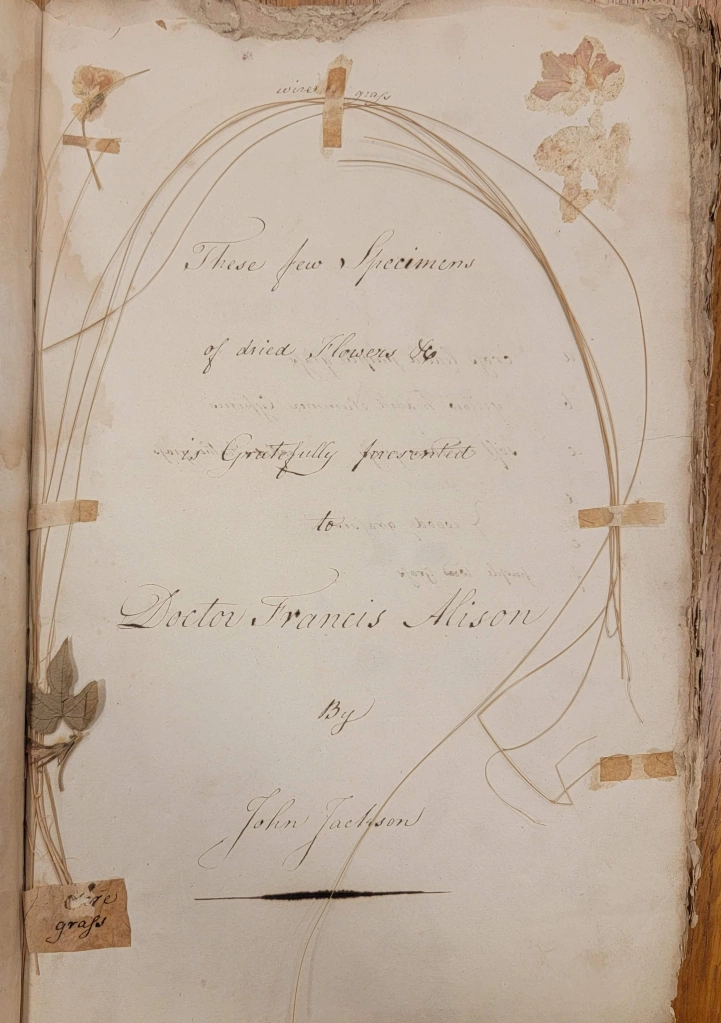

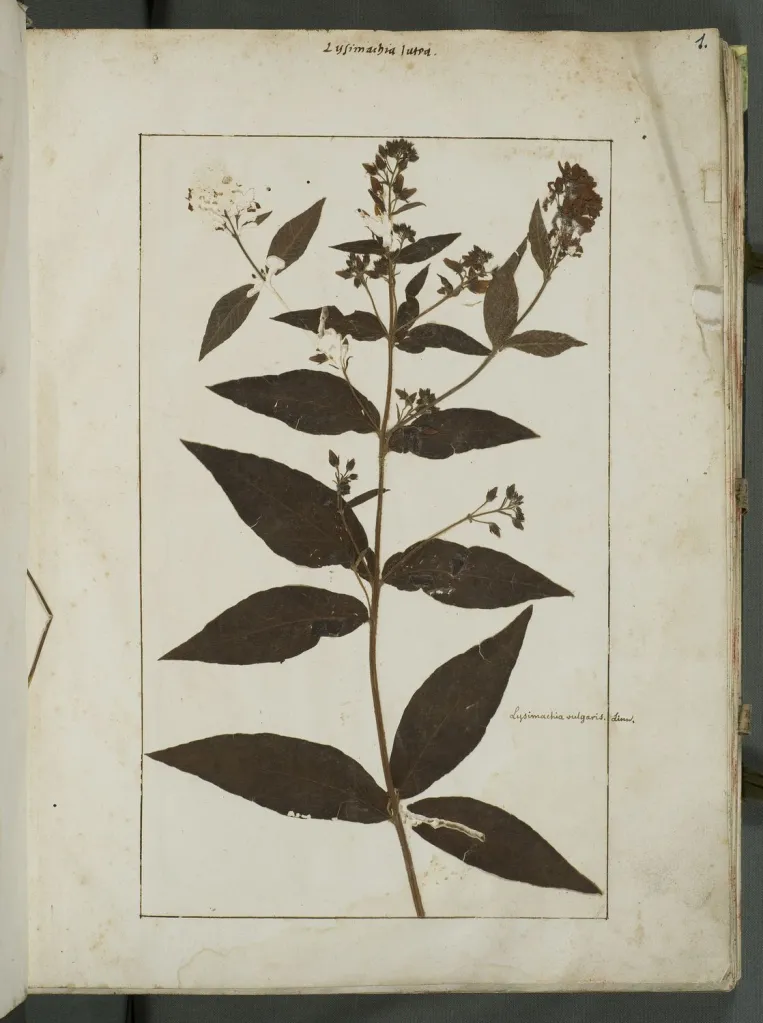

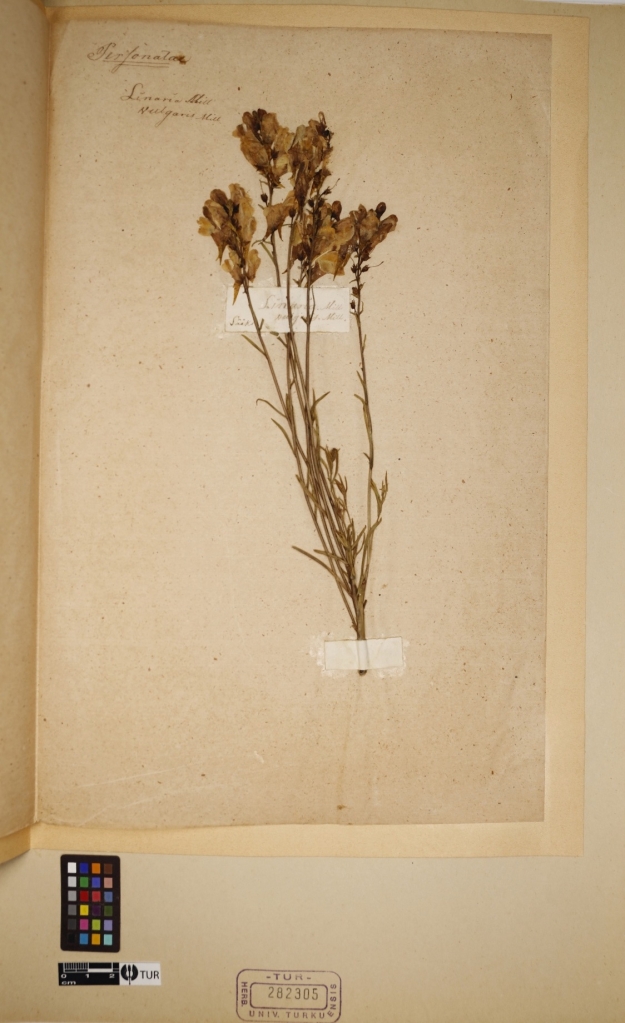

In the doing the research for my book, I’ve found that herbaria can have influence in many fields (Flannery, 2023). One curator in Britain told me that she now has as many requests to view material in the collection from artists and writers as from biologists. Many departments in her university have come to appreciate the collection as an important learning resource for their students. The connection to art is a profound one. The first herbaria date to the mid-16th century about the same time the first botanic gardens and first printed herbals with good illustrations appeared. As botanists studied plants, they sought effective ways to communicate their knowledge to others. Before a good vocabulary of plant terms had developed, visual information was key and remains so. Today many research articles contain drawings of plants and plant parts because these help to clarify often subtle differences among species. Herbarium sheets sometimes include not only a pressed plant and label but a sketch, perhaps of an intricate flower part, or even a printed illustration.

Just as importantly, specimens labels can have crucial cultural information such as indigenous plant names or uses. This can be valuable in many ways today as natural history collections deal with their connections to past colonization and exploitation of indigenous people (Das & Lowe, 2023). These data are essential to historians attempting to write a more inclusive history of the movement and use of plants around the world. Significant work has been done, for example, on the many connections between plant collecting and the slave trade, as well as one the effects of colonial plantation economies (Murphy, 2023). Specimens are documents as useful to this work as written archives with which they often intersect.

I volunteer at the herbarium of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, where the herbarium curators have worked with the university’s McKissick Museum on an exhibit about Henry Ravenel, a 19th-century planter and botanist. More recently, there was collaboration among the museum, the rare book collection, and the herbarium on an exhibit about the plant collector and artist Mark Catesby who arrived in South Carolina in 1722. The university’s copies of his masterpiece The Natural History of Carolinas, Florida, and the Bahama Islands were displayed along with specimens of the plants pictured in his illustrations. This exhibit suggests that there is yet another similarity libraries and herbaria: they are both cultural assets that deserve to be shared broadly with members of the university and the community as a whole.

I am only scratching the surface of the contributions that herbaria can make. The curator emeritus at the university’s herbarium is teaching a course on native plants for gardeners and conservationists; in addition, he writes a “Mystery Plant” newspaper column. The current curator is active on social media (Facebook and Instagram), hosts tours of the herbarium for students and has been known, like his predecessor, to dress as “Plantman” from time to time, all in the service of getting the word out about the collection.

Herbaria do not lack in importance to many disciplines, but what they have lacked is visibility. In the past, they tended to be rather insular, accessible only to botanists working on identifying plants and describing new species. With increased awareness of environmental problems, this picture has changed, especially as collections have been digitized and made available on line. Not only researchers around the world, but anyone interested in plants can see the wonders of specimens and the information recorded on them. Curators now realize that to keep their collections alive they need to communicate herbaria’s multitude of values more effectively. Duke Herbarium’s closure points out the dangers every collection faces, and for so many reasons this shouldn’t be allowed to happen at other institutions.

I’ll end by mentioning what drew me to studying herbaria: the specimens are so beautiful and are connected to wonderful stories: about where the plants were found, who preserved them, and how they have been used over the centuries. Catesby’s collections, now in Britain, are still studied today not only by botanists but by art historians researching the specimens’ connections to his paintings and ethnobotanists interested in what they can reveal about Catesby’s work with indigenous peoples (McBurney, 2021). The poet Emily Dickinson’s herbarium is at Harvard University and was the subject of a recent literary study on how it reflects and foreshadows her poetry (Cole, 2023). Herbaria are treasures with endless uses.

References

Cole, J. L. (2023). Reading Emily Dickinson’s herbarium. J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists, 11(2), 239–250.

Das, S., & Lowe, M. (2018). Nature read in black and white: Decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections. Journal of Natural Science Collections, 6, 4–14.

Davis, C. C. (2023). The herbarium of the future. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 38(5), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2022.11.015

Flannery, M. C. (2023). In the Herbarium: The Hidden World of Collecting and Preserving Plants. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

McBurney, H. (2021). Illuminating Natural History: The Art and Science of Mark Catesby. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Murphy, K. S. (2023). Captivity’s Collections: Science, Natural History, and the British Transatlantic Slave Trade. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Quave, C. L. (2021). Plant Hunter. New York: Penguin.