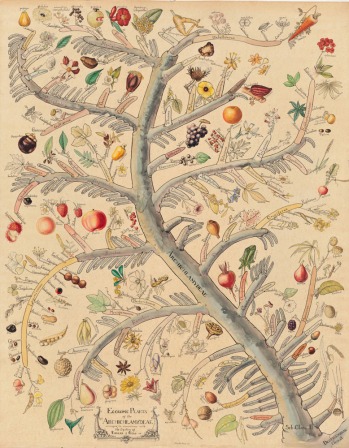

Chart entitled “Economic Plants of the Archichlamydeae” created by Blanch Ames, in the collection of the Harvard University Botany Libraries

In the last post I discussed Oakes Ames, the Harvard botanist and orchid expert who was married to Blanche Ames Ames. Yes, her maiden name was Ames, but they weren’t related. They met while in college and married in 1900, a year after Blanche’s graduation with a degree in art. They both came from wealthy families, but instead of starting out on their own, they went to live with Oakes’s widowed mother on her estate in Easton, Massachusetts. It had several attractions, at least for Oakes. There were greenhouses for the orchids he studied, and he had space for his growing herbarium, as well as plenty of room for Blanche to create orchid illustrations for Oakes’s publications. In 1901 their first daughter Pauline was born, in 1902, the couple’s first work together was published, and in 1903 a son Oliver arrived.

Even with two children, there was still ample space for a growing family at his mother’s house. But there was a crisis in August 1904 when the children’s nurse came down with pneumonia, a frightening infection in the pre-penicillin era. To keep the children safe, Blanche decided to take them to her parents’ home in Lowell, MA. Oakes did not take kindly to this as a series of letters between them documents. Anne Biller Clark studied the correspondence for her book on Blanche (2001, pp. 71-73). Oakes thought his wife should have gone to stay with his brother who also lived in Easton. Though her fears “had no foundation in fact,” she could not see her way clear to “remain under a few inconveniences.” Then he raises the real problem: he insists that she must finish the drawings for his book and not “fritter away time with gossip.”

Not surprisingly Blanche, an ardent suffragette and what her husband called a “new woman,” responded in kind: “You did not take the trouble to put down your herbarium sheet and your glass, but with one eye screwed up and other on a dried flower, you answered me in scarcely more than monosyllables. . . . A few moments in the herbarium showed me that I could expect no aid.” Unfortunately, my husband Bob and I were rarely apart, so our exchanges of like kind are not preserved for posterity, but most married couples can come up with similar examples of infuriation. What makes the Ames’s case particularly interesting to me is that the herbarium is at the center of the ruckus. In the last post, I quoted Oakes’s enthusiasm at seeing type specimens in Paris, another passionate but very different herbarium encounter. Herbaria are usually seen as important resources for scientific research, but I think it’s important to point out that they are nothing without the humans who work with them and cannot check their personal lives and feelings at the door, even if they wanted to. There is a human element to herbaria and that’s one of their big attractions for me.

After this fiery encounter of 1904, it may come as a surprise to learn that Blanche and Oakes remained married for 50 years, until Oakes’s death in 1950. They had two more children, and after living at his mother’s home for six years, they moved six miles away at Blanche’s instigation. His mother showed her displeasure by having her servants prevent Oakes from taking his live orchid collection from the greenhouses; this particularly galled him because he had bought them himself. She also told him that she no longer wanted to receive milk from his cows. Eventually she relented, and mother and son reconciled. Oakes and Blanche designed a castle-like home on their 1200-acre estate called Borderland. The house was constructed of cement and covered in granite: it had to be fireproof to protect not just Oakes’s family, but his herbarium. It also housed his two-story library (Plimpton, 1979).

As she was raising her family, Blanche was an ardent suffragette, drawing political cartoons and arranging rallies that were attended by Oakes, as well as by her mother and even her mother-in-law. Shortly before this fight was won, Blanche took up the cause of birth control as important in women’s path to autonomy. Still, she continued to play a significant role in Oakes’ research. She traveled with him on collecting trips to South America, Asia, and Europe. In Berlin, they were met at the train station by the noted orchid expert Rudolf Schlecter who held an orchid bloom, Stanhopea ruckeri, in his hand to identify himself. Over the next few days, Blanche worked alongside Oakes in Schlecter’s lab (Angell & Romero, 2011). She drew watercolors, including of the Stanhopea, while Oakes pressed specimens. At Harvard’s Oakes Ames Orchid Herbarium, there are a number of sheets that include watercolor and specimen. After Oakes retired they spent more time in Florida, and worked on a book of Blanche’s illustrations paired with his commentaries; it was prepared to go along with a lecture she gave at the orchid society (Ames, 1947).

Blanche did more than draw orchids. She also painted landscapes and portraits, including one of her husband, looking his very serious self. After Oakes died, she sculpted his gravestone, including reliefs of orchids. The works of hers that I like most are watercolor charts created for his economic botany class, such as one with a phylogenetic tree of useful plants (see above). It is full of wonderful details including a squirting cucumber caught in the act. I like to think of the couple collaborating on this, discussing what plants to include and how to represent them.

References

Ames, B. (1947). Drawings of Florida Orchids. Cambridge, MA: Botanical Museum of Harvard University.

Angell, B., & Romero, G. A. (2011). Orchid Illustrations at Harvard. The Botanical Illustrator, 17(1), 20–21.

Clark, A. B. (2001). My Dear Mrs. Ames: A Study of Suffragist Cartoonist Blanche Ames Ames. New York, NY: P. Lang.

Plimpton, O. (Ed.). (1979). Oakes Ames: Jottings of a Harvard Botanist. Cambridge, MA: Botanical Museum of Harvard University.

Pingback: Botany and Art: Specimens | Herbarium World

Pingback: Oakes Ames Shooting Lodge // c.1905 – Buildings of New England