I’ve always found the connection between libraries and herbaria intriguing. I’ve wanted to write about it and now seems a good time because a few weeks ago I went to four libraries in three days as part of what I consider a whirlwind trip to Delaware. I was invited to speak as part of the annual Darwin Day celebration at the University of Delaware and visited its library’s Special Collections. I drove up from South Carolina because I wanted to also go to libraries at Swarthmore College, West Chester University, and Oak Spring Garden. Not surprisingly, all these institutions’ libraries house herbaria in one form or another, and I’ll describe them in this series of posts.

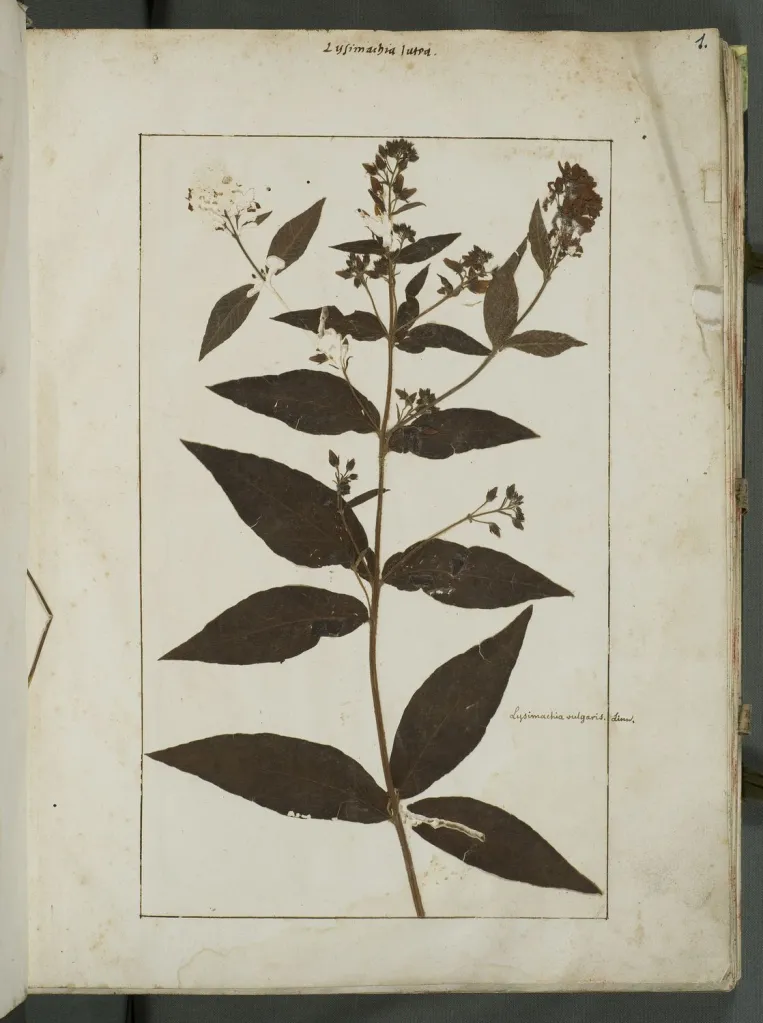

I’ll begin with the most obvious similarities between libraries and herbaria, and then use the collections I saw to dig into some intriguing connections between the two. Libraries and herbaria are both repositories for information on paper. Early herbaria were often bound like other paper leaves would be, but this practice was eventually given up because it made the rearrangement of specimens into groups of similar species difficult. So herbarium sheets, now usually unbound and kept in folders, are stored horizontally, and the same is true of most bound volumes. The latter include exsiccatae or published herbaria, many from the 19th and early 20th centuries that were collections of specimens with printed labels. These were gathered by professional plant hunters who often preserved 20 or more specimens of a species and served as a source of income for many collectors.

There are a number of ways in which the mechanics of a library and an herbarium are similar. Their holdings are catalogued and stored in an orderly arrangement so items can be easily retrieved. Over the centuries, libraries on the whole have been better at this than herbaria. Usually, each book or periodical acquired is recorded, given an identifier, and shelved according to some classification system. The same is true of many herbarium sheets, however the recording system was often not as foolproof. Libraries usually log in their book acquisitions shortly after arrival, though if an entire collection is acquired this may take some time. Herbaria are more likely to have major backlogs. When the herbarium at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris was renovated, curators found 800,000 unmounted and often unidentified specimens. This represented roughly 10% of the entire collection (Le Bras et al., 2017). According to a manager of the project, there were piles, packages, and boxes everywhere, many over a century old.

It’s rare to find an herbarium without a backlog. Many have boxes of unprocessed specimens stored on top of cabinets, glaring down on overworked staff. This is one reason why so many new species are found among already collected material. Now it is true that libraries do sometimes find hidden gems, especially in archives where backlogs are more likely. European libraries are particularly prone to this problem because they often store much older material that may be unexamined for centuries. That’s why wonderful finds are sometimes made including eight volumes of the Swiss physician Felix Platter’s (1536-1614) herbarium found at the University of Bern’s Institute of Plant Sciences in 1930 (Rytz, 1936). It has now been beautifully curated at the Bern City Library.

One of the reasons a number of discoveries, both in herbaria and libraries, have been made over the past few decades is because both these types of institutions have had massive digitization projects. Here the libraries have been in the vanguard since library science as a discipline was revolutionized beginning in the 1960s. The creation of library databases was key to the development of the very concept of a database, and librarians became early adopters of innovations in information technology. I worked for many years at an institution with a computer science program and an IT department, but I gained most of my knowledge about databases and metadata from librarians because they had not only technical expertise but communication skills—and the patience of Job.

In many cases, herbarium curators particularly at smaller institutions also learned about information technology from librarians. The latter had both the skill and the necessary tools. By the 1980s, libraries had scanners and were beginning to image books. Since most herbarium specimens were flat sheets, they could be treated in a similar way. In some cases, the herbaria also used library software to store information, though this was less than ideal because the metadata fields were often inadequate. But still, many libraries provide the first support for herbaria that then began to learn from other natural history collections as support from NSF grew for digitization projects.

One way many libraries differ from many herbaria is in encouraging access. For the most part, herbaria have been worlds closed off from the public, while libraries foster traffic, though special collections housing rare books are more in the herbarium mold, usually limiting visits to those with a stated reason involving research. I’d like to end with one more similarity, I have found both libraries and herbaria to be places where the staff are geared to being helpful. They are stewards of rich resources that they care deeply about and have the expertise to help visitors use them. They love their collections and also know so much about them. Both types of institutions are also places of peace where we can think about the riches with which we are surrounded.

Note: I want to thank the many librarians who contributed information to these posts, and especially to Ron McColl, Special Collections Librarian at the Francis Harvey Green Library at West Chester University for his insights and comments.

References

Le Bras, G., et al. (2017). The French Muséum national d’histoire naturelle vascular plant herbarium collection dataset. Scientific Data, 4(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.16

Rytz, W. (1936). Pflanzenaquarelle des Hans Weiditz aus dem Jahre 1529. Bern: Haupt.