In this post on herbaria and libraries, I’ll look at cases, and there are many, where herbaria are found in archival collections. These are usually bound, like books, and of more historical than scientific interest, though that is changing somewhat now. The 16 volumes of the Italian botanist Ulisse Aldrovandi’s 16th century collection at the University of Bologna have been deconstructed for conservation reasons and the sheets stored in archival boxes. They have also been the subject of a recent study where the species, most collected around Bologna, were compared with those growing in the same area in the 19th and 21st centuries (Buldrini et al., 2023).

Here I want to look at a few herbaria that aren’t nearly as old but still fascinating. As I mentioned in the last post, I visited the University of Delaware in February and while I was there I was able to see treasures from its Special Collections. My guides were Manuscripts Librarian Rebecca Johnson Melvin and Senior Research Fellow Mark Samuels Lasner. We met in the room housing the Lasner Collection of books, art, and other materials from the Victorian era. It’s furnished with bookcases and two long tables in William Morris style down to the Morris-inspired fabric on the chair cushions. One table displayed items from Lasner’s and the library’s collection of Charles Darwin-related material, since I had been invited to speak at an event as part of the university’s Darwin Day celebrations. There was wonderful material including early editions of many of Darwin’s books. Lasner had a page of The Various Contrivances by which Orchids Are Fertilised by Insects (1862) opened to one of the beautiful lithographs done by George Sowerby II, who had spent 10 days at Darwin’s home working on these illustrations, leaving Darwin at the end “half-dead” (Costa & Angell, 2023). My favorite piece in Lasner’s display was a 19th-century cartoon by Joseph Keppler from the humor magazine Puck: Darwin and a pantheon of great minds are highlighted against the enemies of science. It is labeled “Reason Against Unreason” and seems very timely.

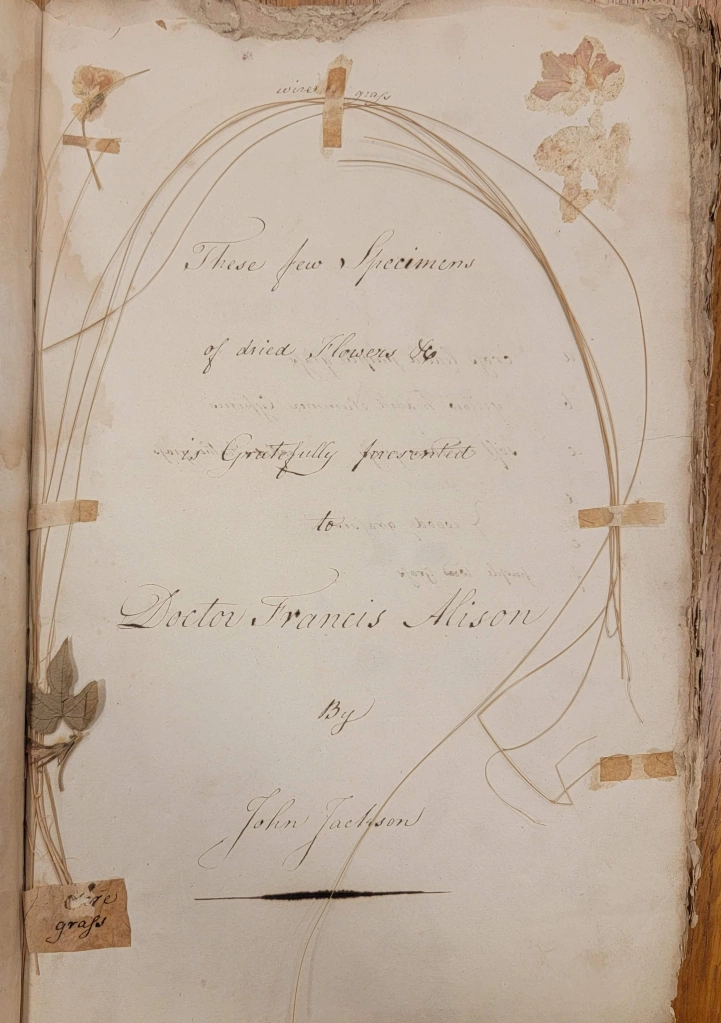

Before my visit, I had asked Melvin if I could see the herbaria of John Jackson (1748-1821), but she had already put them on her list of items to show me. They contain plants collected by Jackson at and around his botanical garden and farm, Harmony Grove, in Chester County, Pennsylvania. I had first encountered him, or at least one of his specimens, in the collection of the physician and botanist William Darlington (1782-1863), which is at West Chester University and is the subject of my next post. This specimen has a note from Darlington explaining that the plant had come from Jackson’s garden and had been grown from seeds brought back from the Lewis and Clark Expedition. That intrigued me and so I looked up Jackson, discovered where his herbarium was kept, and took this opportunity to get a look at it. There are two albums; the thin one with a lovely title page dedicating it to Jackson’s neighbor, the physician Francis Alison. The larger album has no dedication, but I found a specimen collected by Darlington when his initials WD, which he often used, caught my eye. It was like meeting an old friend. Because of the fragility of the paper, I didn’t examine every page, but I got a good sense of the care Jackson took in making the collection. He was a generation older than Darlington, but they were both Quakers living in an area steeped in the study of natural history and especially botany. The next day, I went to Special Collections at Swarthmore College, where there is a collection of papers relating to Jackson and his relatives. I found little about his interest in botany, but did come upon a surprise: a small notebook filled with plant specimens, each numbered and labeled with common names. It is dated 1833-1866, but the creator is unknown. It might be a young person’s collection; it was a surprising little jewel revealing the family’s continued interest in plants.

Melvin also had on display notebooks created by Elizabeth Carrington Morris and her sister Margaretta who were 19th century naturalists in Philadelphia. Elizabeth was particularly interested in botany while Margaretta focused on entomology. They both corresponded with leading scientists in their respective fields, and for Elizabeth that included Asa Gray and Darlington who encouraged the work done by both sisters. Each one created notebooks that can only be described as exquisite. Elizabeth painted exceptionally fine paintings of plants and also landscapes; these were interspersed among poems done in fine calligraphy. Catherine McNeur (2023) has recently written an interesting book on the pair, arguing that they had a significant influence on the development of natural history in the United States.

Next to the notebooks were two student herbaria done by an African-American sister and brother, Anna and Arthur Dickenson in Xenia, Ohio in the early 20th century. They had carefully filled in the information in their printed herbarium workbooks and added the specimens, making these good examples of what once was relatively common in American education, in this case in a segregated school. The final item on display was one I knew about but had never seen and consequently had not fully appreciated. It is the artist book The Arctic Plants of New York City created by James Walsh (2016). At least a decade ago on a snowy night in Brooklyn, I had attended the opening of a show of his work. Though he hadn’t yet produced his book, his theme at the time was Arctic plants, by which he meant those that grew in northern Europe and were brought to the New World by European colonists, and some became weeds here. At the exhibit, the specimens were on the wall. In the book they are meticulously mounted, one on a page, with key words printed around each and more information on the opposite page. The “page” for each plant is heavy cardstock with a mat around the specimen, giving it even more depth. It is indeed an art book—and an herbarium.

Note: I want to thank John Jungck for the invitation to speak at the University of Delaware and to Karn Rosenberg for her many kindnesses during the visit. I am especially grateful to Rebecca Johnson Melvin and Mark Samuels Lasner for sharing their treasures and expertise with me. Finally, thanks to so many kind people who made my time at the university so wonderful.

References

Buldrini, F., Alessandrini, A., Mossetti, U., Muzzi, E., Pezzi, G., Soldano, A., & Nascimbene, J. (2023). Botanical memory: Five centuries of floristic changes revealed by a Renaissance herbarium (Ulisse Aldrovandi, 1551–1586). Royal Society Open Science, 10(11), 230866. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.230866

Costa, J. T., & Angell, B. (2023). Darwin and the Art of Botany: Observations on the Curious World of Plants. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

McNeur, C. (2023). Mischievous Creatures. New York: Basic Books.

Walsh, J. (2016). The Artic Plants of New York City. New York: Granary.

Pingback: The Library as Herbarium | Herbarium World